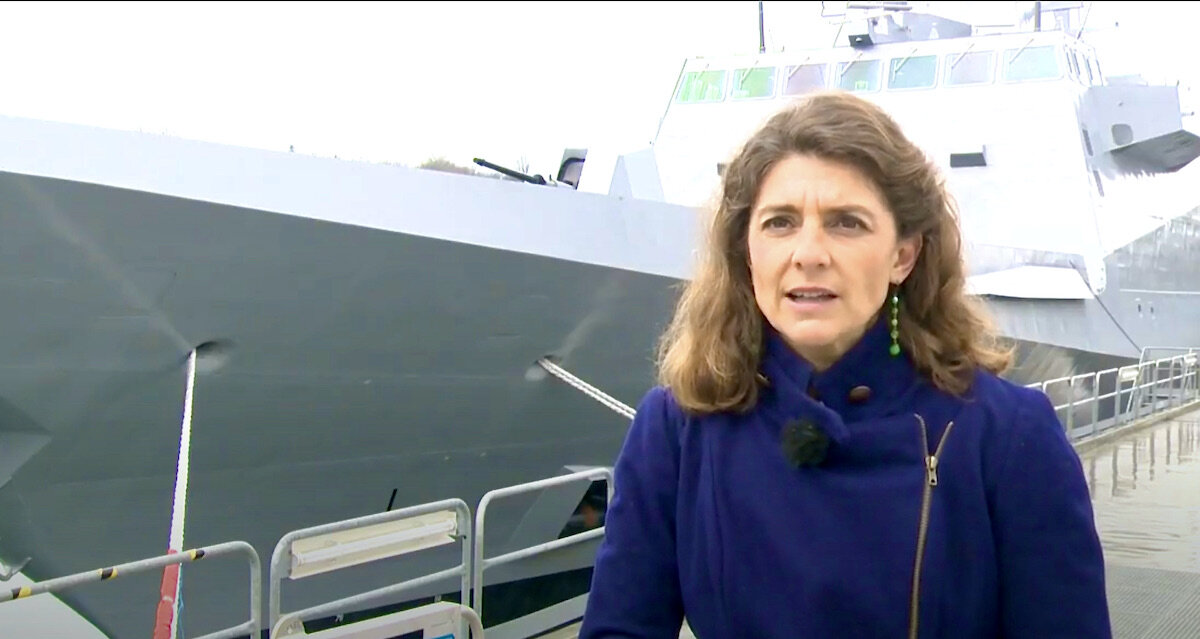

Anne Bianchi

Anne Bianchi proves that you can remain feminine and be extremely successful in a man’s world. Photo credit: Naval Group

When Anne was studying at the École Polytechnique (see glossary), it was mandatory for all students to spend a year in the military. A keen traveller, she thought that spending this time on a ship would be a great way to see new places. “And that’s how I found myself aboard ship for eight months after three months at the Naval College. And I loved it!” From then on, apart from a brief incursion into the oil industry, Anne has always worked in the naval sector. Today she is in charge of the new French nuclear attack submarine (SNLE) programme at Naval Group. Not one to blow her own trumpet, she omitted to tell me that in September 2018 she had won the “Jury’s Special Prize”, one of the 12 trophies awarded by the magazine ‘L’Usine nouvelle’ to women who’ve had a remarkable career in industry.

““I’ve often been warmly welcomed in this man’s word even if I’m always pleased when there are other women around!””

The four future SNLE’s (these are nuclear powered submarines armed with ballistic missiles that have a nuclear war-head) will be France’s seaborne nuclear deterrent from 2035. These types of submarines are the most complex objects built by humans: “Each vessel is like the Kourou spaceport, a nuclear power station and a village of 110 people all packed into a 140-metre long boat, underwater,” the company stresses.

Raised in a family of teachers in Cannes, good at maths but “with only a moderate taste for technology”, Anne nevertheless opted to specialise in naval architecture after graduating with an engineering degree from Polytechnique. She went to the ENSTA engineering school in Brittany where “there were only 20 of us in naval architecture including one other woman, a Norwegian who was studying for her Master’s degree. This course gives you a good general idea of all the aspects of naval architecture but one only specialises later and I never really studied the technical side of things,” she explains during our video conversation.

Attracted by the world of ships, industry and project management, she joined the Naval Construction Department (Direction des Constructions Navales, better known as DCN) which at the time was part of the French Defence Ministry’s procurement arm, the DGA (see glossary). So she automatically gained military status.

Anne began her career in 1996 in charge of the production information systems for the Sawari frigates for Saudi Arabia being built in Lorient, in Brittany. But just three years on she took a sabbatical to accompany her husband who’d been posted to Cameroon and found a job there with the Bolloré group. She was in charge of the logistics information system for the Doba-Kribi pipeline which carries crude oil from Doba in southern Chad to the offshore facility at Kribi in Cameroon. At the end of their West African adventure, the couple decided it was time for a prolonged sailing break. “My husband went sailing for a year and I joined him for eight months with the two children we had at the time [they now have four] who were 4 and 5 years old.” The adventure took them from Hyères in the Mediterranean to Martinique in the Caribbean via Venezuela, amongst other places.

But in 2002 with the end of her sabbatical, Anne returned to DCN in Cherbourg as deputy director of the Scorpene submarine programme for Malaysia and then as project manager for platforms. And then in 2009, after DCN had become the company DCNS, she resigned her military status (which, for somewhat obscure reasons had not developed as she’d hoped) and became a civilian employee just like the rest of the workforce.

Still taken from a 30th Jan. 2014 DCNS video when the first FREMM , the Mohamed VI, was delivered to the Royal Moroccan Navy.

In 2009 she was appointed as DCNS’ representative in Spain. “I was in charge of client relations, and thanks to my mother being a Spanish teacher, I was fairly at ease with the language,” she smiles. But she later had to switch to Brazilian Portuguese because in 2016, after having headed the hull, structure and outfitting department in Cherbourg and been responsible for the FREMM multimission frigate programme for the French Navy, she headed off to São Paolo and Rio de Janeiro as director of the submarine programme for the Brazilian Navy. She stayed in Brazil until 2020.

Meanwhile, in 2017 DCNS changed its name to Naval Group.

In 2019 Anne became director of the submarine export programmes before being appointed to her current job last April. So she was not the one who bore the full brunt of the shock announcement last month when Australia announced it was tearing up the contract it had with Naval Group which was building 12 diesel-powered submarines for the Australian Navy. Nevertheless “it was terrible for the moral of everyone in the Group,” she remarks soberly.

It’s a little surprising that during all this time when Anne has been working with submarines she’s never once gone on a dive. “With the export submarines, which is what I’ve been most involved with over the past few years, there’s not really very much space inside so only those who are vital for the tests go aboard and that didn’t include me. In 2004 I was able to undertake a 24-hour ‘fictitious dive’ with the crew of the first Chilean Scorpene but that was a quay-side exercise! I’ll surely soon go aboard a French submarine and I’m really excited about that!’

One might have imagined that her brilliant career in the almost exclusively masculine world of submarines would have cost Anne something of her personal life. Not at all. “I’m prepared to work up to a certain limit,” she says firmly. “Also, a large part of my working life was spent in Lorient or in Cherbourg where it’s much easier to get around than in Paris to go and fetch the kids from school, for example. And we also had help from au-pair girls.”

Anne was an ephemeral actress during her time at Polytechnique. But this experience did not relieve her of stage-fright when she had to make her first professional presentations. “I was much more nervous than I ever was on stage,” she laughs. More seriously she adds that she’s “unsure that my job has been more difficult because I’m a woman; I’ve often been warmly welcomed in this man’s word even if I’m always pleased when there are other women around!”